African Americans in and from Kentucky in the Cigar Industry, 1860-1940

(start date: 1860 - end date: 1940)Written by Reinette F. Jones, September 17, 2018

Attached to this entry:

1. Kentucky Counties Map - 1900 Cigar Industry (.pdf)

2. Image of Nancy Anderson "Old Boss" (.pdf)

3. Map video showing U.S. states with African Americans in and from Kentucky employed in the Cigar Industry, 1860-1940 (.mp3)

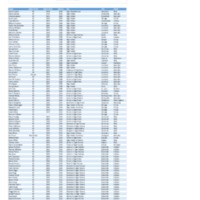

4. Data table of African Americans in and from Kentucky in the Cigar Industry, 1860-1940 (.pdf).

Contrasting and parallel lines of employment developed in the cigar industry for African Americans in and from Kentucky starting around 1860. The fact was that there were very few cigar jobs for African Americans in Kentucky, while outside Kentucky there were many more job opportunities. By 1920, the result was that 94% of the African Americans from Kentucky who were in the cigar industry were employed out-of-state, the majority working in Evansville, IN. There was no tracking or reporting of these particular statistics. In the U.S. Census reports and other publications, the number of cigar industry employees was lumped into the overall number of tobacco industry employees count.

Thousands of African Americans were doing tobacco work in Kentucky. At the start of the 1900s, African Americans accounted for two-thirds of the total employees in the tobacco industry centers in Winston-Salem, Durham, St. Louis, and Louisville. Wages were low, the work hard and unhealthy. In the tobacco industry centers, tobacco work was considered Negro work. However, that did not apply to cigar work. [Source: The Negro Wage Earner, by L. J. Greene and C. G. Woodson.]

Cigar work was not Negro work in Kentucky. Lumping the employee data into one category, "tobacco and cigar," may have made sense for other locations, but it did not come close to defining the situation in Kentucky. By not keeping track of the employees in the cigar industry specifically, the compilers had failed to document and account for the outmigration of African Americans from Kentucky. On the other hand, perhaps the outmigration was considered insignificant, because employment in the Kentucky cigar industry was flush with white employees who were European immigrants, children of European immigrants, and cigar makers from the northeastern United States--these were the persons considered "the" cigar industry employees in Kentucky, individuals working for themselves and those working for manufacturers in Louisville and northern Kentucky and to a lesser degree in Paducah and a few other Kentucky cities. Their names can be found in the U.S. Census records starting around 1810 and in city directories as early as 1860. [Sources: William's Covington Directory City Guide [1861]; and Tanner's Louisville City Directory for 1860-1861. Both are available online at Ancestry].

Was slave labor used in the Kentucky cigar industry? Maybe. Enslaved workers were the main labor force in the tobacco industry in Kentucky prior to 1865, so it is highly likely that there were enslaved workers used in the cigar industry. There is little chance that the names of those enslaved and working in the industry will be found, for they were property and not considered employees who would have been named in records. At this time, sufficient documentation has not been found to track their history or address questions about the use of slave labor in the Kentucky cigar industry.

Accompanying this entry is the image of Nancy Anderson, a woman who had been enslaved in Kentucky. Her image was used on the boxes of Old Boss brand cigars, but there is no indication that she ever worked in the cigar industry. For more information about Nancy Anderson, see p. 14 in Black American Series, Lexington, Kentucky, by G. L. Smith. The images of African Americans were used for the marketing of many products in the United States, including cigar advertisements. [See the 1895 ad "A Sure Winner" WikiMedia Commons webpage.] [Sources: Lexington's First City Directory, 1806; Lexington's Second City Directory, 1818; and The Tobacco Industry in the United States, by M. Jacobstein. See also The Kentucky Encyclopedia for more about the counties that used slave labor for the production and processing of tobacco.]

This entry focuses on the employment of African Americans in and from Kentucky in the cigar industry. The individual U.S. Census sheets were used to find the names of the employees. Starting in 1860, there were three names of free African American cigar makers, the first being Daniel Lawson and his wife Amanda, cigar makers in Shelbyville, KY. There was also Kentucky native Jarred Hughes, a cigar manufacturer in Cleveland, OH. In 1870, Kentucky native Jessie Lewis was a cigar maker in Chicago, and Lewis Hoskins was a cigar maker in Indianapolis. By 1880, William Hardin was working in a cigar factory in Xenia, OH; William Preaston was a cigar maker in Chicago; and four African American cigar makers worked in Louisville, KY: Nelson McGrewden, Alfonzo Williams, Frank Dodge, and Clarence Leonard.

The making of cigars had come to Kentucky by way of Ohio and the northeast. The first U.S. domestic cigars made by Europeans were produced by women in the early U.S. colonies at the time two cigars sold for a cent [Baer, p. 30]. Cuban cigars were brought to Connecticut around 1790. The manufacturing of U.S. cigars started in the Connecticut Valley District, the first factories located in Connecticut and others later in New York and Pennsylvania. When the Ohio District was established in the early 1800s, it was the beginning of the "production of cigar-leaf on a commercial scale." Settlers from Connecticut made their homes in Montgomery County, OH and brought with them the culture of cigar types. By 1850, the Miami Valley area in Ohio was the center for filler tobacco production, and later Medina County was the center for binder and wrapper leaf production. [Sources: "Cigar Manufacturing, United States" on pp. 74-76 in Encyclopedia of Smoking and Tobacco, by A. B. Hirschfelder; and The Economic Development of the Cigar Industry in the United States, by W. N. Baer, chapter 1, "Development prior to 1800." Quotation from p. 38.]

In Kentucky, the first cigar manufacturers were part of the Ohio Valley District industry. Manufacturers from Pennsylvania moved to Maysville, KY on the Ohio River, bringing the cigar-making business with them as early as 1824. Those cigars were made with Cuban tobacco. The operations in Maysville could not compete with the more established businesses across the Ohio River in Cincinnati, OH. In 1851, there were 62 tobacco manufacturers and 28 wholesale dealers in Cincinnati, with one firm having an output of 120,000 cigars per month.

As a major center of cigar making, Cincinnati held sway over the attempt to organize the first cigar makers' union. This influence continued as the cigar industry started to spread to other regions, including areas in Kentucky. After the U.S. Civil War, Cincinnati continued to grow as a major tobacco center, while across the river in Maysville, KY, there remained individual cigar makers and manufacturers: 15 in 1860, 38 in 1870, and 79 in 1880. [Sources: The Economic Development of the Cigar Industry in the United States, by W. N. Baer, chapter 1, "Development prior to 1800"; and the 1860, 1870, and 1880 U.S. Census.]

The first cigar makers' labor union was formed in Cincinnati in 1845, which was followed by the development of other independent cigar unions in various regions. In 1863, a conference was held in Philadelphia, PA to discuss bringing the organizations together under one heading, and in 1864 the Cigar Makers National Union (CMNU) was founded in New York, later becoming the Cigar Makers International Union (CMIU) in 1867. Initially, only males were members, but that changed after cigar manufacturers began hiring women as strikebreakers. This occurred in Cincinnati in 1870 when women were hired to replace the men who were on strike against the use of the cigar mold.

The industry was being introduced to new technology with this use of cigar mold (see images), along with other changes in the division of labor and the hiring of more women and cigar makers from Europe. In response to the industry changes, the union too had to change. The CMIU membership split, and later there was a merger. In 1875, some of the local union groups began allowing women members. In spite of all the changes and progress, the Cigar Makers International Union's initial constitution specifically excluded colored people (African Americans). As late as 1900, when other unions reported having Negro members, a representative at the CMIU reported it had none. However, according to a 1910 article in the Cigar Makers' Official Journal, the color line had not been in force in the cigar union since 1873, and it was claimed that CMIU had thousands of colored members throughout the United States.

Contrary to the reports and claims, there were some African American members in CMIU. The first colored local union was formed in Charleston, SC in 1884. Most African American members of the CMIU were members of the local organizations in New Orleans, LA and Mobile, AL. [Sources: Bulletin of the Bureau of Labor Statistics, no. 618, March 1936, "Handbook of American Trade-Unions," Part II: National and International Unions, p. 112 [online at Google Books]; "Cigar Makers International Union," pp. 243-244 in Encyclopedia of U.S. Labor and Working Class History, vol. 1; W. E. B. Dubois, "Some efforts of American Negroes for their own social betterment (1898)" in The American Negro: his history and literature, edited by W. L. Katz; and Cigar Makers' Official Journal, vol. XXXV, No. 2, December 15, 1910, p. 9. For more on the cigar mold and women employees, see M. J. Prus, "Mechanisation and the gender-based division of labour in the US cigar industry," Cambridge Journal of Economics, vol. 14, no. 1, (March 1990), pp. 63-79; and Once a Cigar Maker, by P. A. Cooper.]

Racial and ethnic membership of the CMIU was a reflection of the employment within the entire U.S. cigar industry. The written literature about the union and the industry contains very little information about African American members and employees. For most states, there was not a written history, even as the cigar industry continued to grow and spread to major cities where there were both the customer demand and the labor supply for the making of cigars. "By 1880, most states and territories, except for Montana and Idaho, had cigar factories." The cigar industry was still at a crossroads concerning the best method for the making of cigars: handmade vs machine-assisted manufatured cigars.

In the 1890s, there was an influx of workers to the industry when cigar manufacturing quickly took a stronger hold in Tampa, FL after Cuban refugees arrived in the city, bringing their cigar making skills with them. The Cuban-made cigar was king. In Cuba, the growing of tobacco for cigars, the making of cigars, and the cigar factories had been in place since the 1500s. [Sources: The Cuban Cigar Handbook, by M. Speranza, et. al.; and the quotation from p. 75 in Encyclopedia of Smoking and Tobacco, by A. B. Hirschfelder.]

According to Evan Matthew Daniel in the entry "Cubans" in the Encyclopedia of U.S. Labor and Working Class History, vol. 1, pp. 332-334, there was a pecking order to the workers who made Cuban cigars in the United States during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Spaniards (Peninsulares) made the most expensive cigars in New York. In Tampa and Key West, the Europeans born in Cuba (Creoles) were the dominate employees. At the bottom of the employment ladder were the Afro-Cubans, who along with the Afro-Americans in Ybor City, did jobs like sweeping and hauling. African Americans in and from Kentucky would become part of a similar job/race/gender stratified labor system.

But first, the cigar industry had to mature into a more bona fide industry. The transition would come in the 1890s when cigars became the most important tobacco product in the U.S. The most popular and the smallest branch of the industry was "Clear Havana." These were the most expensive cigars, selling for 15 cents or more. They were modeled after the cigars made in Cuba, though in the U.S. they were made in Tampa and Key West by Cuban and Spanish workers. [Sources: From Hand Craft to Mass Production: Men, Women and Work Culture in American Cigar Factories, 1900-1919, by Patricia Ann Cooper (1981 thesis); and "WPA Stories: Ybor City," a Florida Memory website.]

The remainder of the cigar industry was in other U.S. states. The second branch of the industry was called "Seed and Havana." These cigars were made with Cuban and homegrown (U.S.) tobaccos. These cigars were made in different styles, shapes, and colors. The cost per cigar started at 10 cents. The third branch of the industry produced the cheapest cigars that sold for five cents or less; these did not vary in style or shape and were more cheaply made with less craftsmanship and lower grade tobaccos. [Source: From Hand Craft to Mass Production: Men, Women and Work Culture in American Cigar Factories, 1900-1919, by Patricia Ann Cooper (1981 thesis).]

By 1890, cigars were being manufactured in Louisville and northern Kentucky. There were 76 cigar manufacturers listed in the Louisville city directory, including Bickel C. C. & Co., the leading cigar house in Louisville; Fall City Cigar Manufacturing; Hetterman Brothers; Mueller A. & Co.; Steinberg & Brother; and Union Star Cigar Factory [sources: p. 1334 in Caron's Directory of the City of Louisville for 1890; and The City of Louisville and a Glimpse of Kentucky, by Y. E. Allison]. In northern Kentucky, the cigar industry was spread among several cities that included Bellevue, Covington, Dayton, Ludlow, Milldale, and Newport. The cigar manufacturers included George J. Wohrley's Manufacturer of and Jobber in Fine Cigars in Covington; John M. Dietz's Cigar Manufacturer Wholesale and Retail Dealer in Newport; and J. C. Heidrich, cigar manufacturer in Dayton, KY [source: Williams & Co. Covington, KY, City Directory, 1890]. There were also cigar makers in Paducah, and there would later be a cigar box company. M. W. Martin was president and manager of the Paducah Cigar and Tobacco Company [source: H. Thornton, Bennett & Co.'s Paducah, Kentucky, City Directory, 1890-91].

In reference to African American workers in Kentucky, there was a count of 1,019 tobacco & cigar factory operatives: 857 males and 162 females [source: The Negro Artisan, p. 126]. These cigar and tobacco operatives were said to be among the chief artisans in Kentucky. The statement is true, but the reported numbers are more a representation of African American tobacco workers, because there were only nine African Americans employed in the Kentucky cigar industry in 1900. These few employees were not a factor among the more than 1,600 cigar industry employees in Kentucky. The following is a list of the Kentucky cities/counties where all cigar employees were located. | Augusta (Bracken County), Alton (Anderson County), Ashland (Boyd County), Bellevue (Campbell County), Bowling Green (Warren County), Bromley (Kenton County), Campbellsville (Taylor County), Catlettsburg (Boyd County), Covington (Kenton County), Dayton (Campbell County), Elsmere (Kenton County), Eminence (Henry County), Gillmans (Jefferson County), Henderson (Henderson County), Highland Park (Jefferson County), Hill Top (Mason County), Hopkinsville (Christian County), Latonia (Kenton County), Lebanon (Marion County), Lexington (Fayette County), Louisville (Jefferson County), Ludlow (Kenton County), Mayfield (Graves County), Maysville (Mason County), Newport (Campbell County), Owensboro (Daviess County), Paducah (McCracken County), Richmond (Madison County), Tollesboro (Lewis County), Two Mile House (Jefferson County), and Williamstown (Grant County). * [See also the accompanying map of Kentucky with data displayed by county.]

The few African Americans in Kentucky's cigar industry in 1900 included a cigar maker in Paducah. In Louisville, there were two cigar makers, two porters, and three laborers in cigar shops, as well as a drayman in a cigar store. All were Kentucky natives except John Boone, who was born in Canada. The 14 African Americans who had out-of-state jobs were performing the same duties as those in Kentucky: cigar makers, porters, and laborers in cigar stores. Louis Marchal was a cigar dealer in Hamilton, OH, and L. L. Lindsey was a cigar merchant in Lincoln, NE. Others were employed in Center, IN; Chicago and Chester, IL; Cincinnati and Perry, OH; Guthrie, OK; and St. Louis, MO. All of the out-of-state employees were men, except Kitty Connelly, a female cigar maker in Cincinnati.

At the end of the next decade, there were 20 African Americans employed in the Kentucky cigar industry. The year was 1910 and the 20 employees were an all-time high for Kentucky. The gain had been slow, extremely slow. It had taken half a century, 1860-1910, for there to be more than 10 African Americans in the Kentucky cigar industry. All of the employees were Kentucky natives except Joe Foster from the West Indies, and William Thomas from Virginia and Wesley Scott from Louisiana, who were porters in cigar stores in Louisville. Realistically, the 20 African American employees were a miniscule part of the more than 1,800 cigar industry employees in Kentucky and more than 150,000 in the United States. Yet the significance of the data further shows the resistance toward hiring African Americans in the Kentucky cigar industry. [Source: 1910 U.S. Census.]

There were no labor movements, marches, or rallies for more African Americans to be hired in the Kentucky cigar industry. Even without published statistics in hand, African Americans knew that they had little chance of being hired. At the start of the second decade of the 20th century, at least 60 African Americans from Kentucky were working in the cigar industry in some other state, compared to the 20 who were employed in Kentucky. Twelve of the 20 worked in Louisville, with one each in Covington, Bowling Green, Burkesville, Greensburg, Hopkinsville, Owensboro, Paducah, and Richmond.

In addition to the disparity in employment numbers, African Americans were no longer being hired in Kentucky as cigar makers. In 1910 Joe Foster, from the West Indies, was one of the last African American cigar makers in Kentucky. He was employed in a factory in Covington.

There were also few African American women employees in Kentucky. Lula L. Merrett and Virginia Morris were tobacco stemmers in Louisville, and Bernice White was a factory laborer in Richmond. The male employees were primarily hired as tobacco stemmers or porters; while only one each worked in the positions of drayman, driver, elevator man, laborer, shaker, and tobacco steamer. William Dodd was a sawyer making cigar boxes in a factory in Paducah.

By 1910, among all the states with a cigar industry, Indiana took full advantage of Kentucky's resistance to hiring African Americans. African Americans who left Kentucky looking for work were mostly were hired across the Ohio River in Evansville, IN: 24 were employed in cigar factories and stores: eight men and 16 women. Of the women, 12 were tobacco stemmers, three workers, and one a roller. Among the men, four were laborers, three porters, and one a stock boy. The overall out-of-state employment numbers in 1910 were Indiana (30), Ohio (16), Illinois (8), and one each in Michigan, Missouri, Oklahoma, Tennessee, West Virginia, and Wyoming. More than half the out-of-state employees were males working as porters, with 28 in cigar stores, three in factories, and one at a cigar stand. The other employees included Robert Benjamin, a boot black in a cigar store in Cheyenne, WY; and Herman Lewis, a janitor in a cigar factory in Dayton, OH. All of Kentucky's African American cigar makers were now working out-of-state: Nelson McGrugger and Edward A. Long at factories in Chicago, Mary Minter in a shop in Columbus, OH; Jessie White in a factory in Dayton, OH; and Herman Caldwell in Memphis, TN. The out-of-state female employees included Mary Minter in Columbus and the four women employed in Cincinnati: Lucy Hamilton and Willia May Kelly were tobacco strippers, and Mary E. Williams and Coletta Griffin were tobacco stemmers.

In 1920, the out-of-state employment reached an all-time high for African American cigar workers from Kentucky. The state of Indiana benefited even more so than the previous decade. Of the 237 African American employees who were Kentucky natives, 222 or 94% worked in the cigar industry in Indiana (159), Ohio (31), Illinois (17), Michigan (5), New York (2), with one each in Colorado, Kansas, Louisiana, Missouri, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia. Among the 6% of the African American employees in the Kentucky cigar industry, 11 were employed in Louisville, two in Henderson, and one each in Bowling Green, Covington, Elsmere, and Paducah. Employees who were not Kentucky natives were Henry Kizer from Tennessee, a cigar box maker in Paducah; and Noah Sands from Indiana, as a janitor in a cigar store in Louisville.

The overall employment numbers for African Americans in and from Kentucky had tripled from 80 in 1910 to 239 in 1920. The cigar industry had put out a call for women employees; from Kentucky, there were 150 African American females along with 89 African American males. Most of the women were tobacco stemmers in factories (105), plus one teen male. Other job duties included 24 laborers; four janitors (males) and two janitresses (females); 25 male porters in cigar stores and two in cigar factories; 15 female tobacco strippers in factories; and five male shipping clerks; along with lesser numbers of employees who were drivers, a binder, bookers, bulkers, fillers, foreladies, sales persons, a sweeper, and a watchman.

Evansville, IN was the absolute number one city for the employment of African Americans from Kentucky in the cigar industry in 1920. There were three cigar factories in Evansville that employed 1,707 non-union employees. The African American employees from Kentucky included 120 women, most of whom were stemmers, and 28 men, who worked as laborers. Female stemmers and strippers worked by hand, not machine, averaging 44 hours per week at 15 cents an hour, one of the absolute lowest wages in the cigar industry. African Americans from Kentucky were a significant addition to the Evansville workforce.

The 148 cigar industry employees from Kentucky were 46% of the 322 African American cigar and tobacco factory employees in Indiana. The cigar industry was only one of the contributing factors accounting for the outmigration of African Americans from Kentucky to Indiana. By 1920, opportunities in Indiana had drawn 24,182 African Americans from Kentucky, and they made up 30% of the 80,810 African Americans in Indiana. [Sources: D. Pope and L. Magnusson, "Wages and hours of labor," Monthly Labor Review, vol. 10, no. 3, (March, 1920), pp. 77-131; 1920 U.S. Census. Volume 3. Population, Composition and Characteristics of the Population by States. Summary Tables and Detailed Tables - Georgia through Iowa. Composition and Characteristics. Table 1, p. 282.; 1920 U.S. Census. Volume 4. Population, Occupations. Chapter 7: Males and Females in Selected Occupations Tables 1. Indiana continued. Manufacturing and Mechanical Industries. Cigar and Tobacco Factories. Males, p. 916. Females, p. 918.; 1920 U.S. Census. Volume 2. Population, General Report and Analytical Tables. Chapter 5: State of Birth of the Native Population. Table 19, p. 639.; "Organizers' Reports. Evansville, Ind., June 23, 1917" in Cigar Maker's Official Journal, vol. XLI, no. 7, July 1917, pp. 14-15; and Fragile Alliances, by S. W. White]

Chicago, IL was the number two city of employment in 1920 with 13 African Americans from Kentucky working in the city's cigar industry. The third city was Louisville with 11 African American employees, followed by Dayton with 10. There were no African American cigar makers in Kentucky in 1920, but there were three each from Kentucky in Chicago, Evansville, and Cincinnati, and one each in Murphysboro, IL, New Orleans, Detroit, and Columbus. Eight of the cigar makers were female and five male.

The 239 African American employees in and from Kentucky were 1.12% of the 21,334 African Americans employed in the cigar and tobacco factories in the United States in 1920. Along with the increase in out-of-state employment, a few African Americans from Kentucky had also become cigar business owners. Will Jones owned a cigar store in Barberton, OH. Nannie Meridith and Henry L. Basket each owned a cigar store in Chicago. William Shields and James Harold each owned a cigar store in Danville, IL. Mitchell Clark and James Gooch each owned a cigar store in Dayton. Eugene Cash owned a cigar store/pool room in Vandalia, WV. [Source: 1920 U.S. Census. Chapter 3: Color or Race, Nativity, Parentage of Occupied Persons. p. 345.]

There were also other changes occurring in the cigar factories with the introduction of mechanization, starting in the late 1800s with the advent of the cigar mold, along with later machines such as the bunchmaker, rollers, and automatic long filler in 1917. The new machines led to teamwork processing. Individual skill requirements in the making of cigars were lessened, thus leading to reduced wages and reduced reliance on male cigar makers, who had dominated the industry. The cigar was the last tobacco product to be mechanized.

More women were hired at lower wages and as a means of getting away from the union. African American women's wages were less than the wages of women of other races, and they often worked in segregated areas in factories. The majority of the African American women were hired as stemmers. "From 1890 to 1920, women's employment as a percentage of total employment increased from 21.8% to 59%." Female stemmers, regardless of race, made less earnings than all other cigar industry employees. In 1929, over 100 African American women employees walked out of the Bayuk Brothers cigar factory in protest of the low wages, long hours, and unsanitary conditions. [Source: M. J. Prus, "Mechanisation and the gender-based division of labour in the US cigar industry," Cambridge Journal of Economics, vol. 14, no. 1, (March 1990), pp. 63-79. Quotation from p. 74.; and "Over 100 unorganized Negro women..." on p. 193 in Opportunity, vol. 7, no. 6, June 1929.]

The labor force and the mechanization continued to evolve. The cigar rolling machine was introduced after World War I. With it and other new and improved machines, the cigar industry workforce started to decline. More and better cigars were being produced for 5 cents or less, and the small cigar making operations were being bought out. The number of African American cigar employees in and from Kentucky had decreased from 239 in 1920 to 138 in 1930. However, the hiring of African Americans in Kentucky had increased from 17 in 1920 to 25 in 1930. Six of the Kentucky employees were from outside the state: Nellie Johnson and Henry Whatley from Alabama, St. James Green from Georgia, Louise Bright and Philista Thompson from Tennessee, and Rosa Harper from Arkansas. The hiring of African Americans from other states was not a trend and never became one in Kentucky. However, the out-of-state employment of African Americans from Kentucky had continued, with Evansville, IN making the most use of that segment of Kentucky's workforce: there were 66 African American employees in Evansville, 22 in Louisville, and 11 in Chicago.

In Kentucky, the advancements in technology had no impact on the hiring of African Americans in the cigar industry. Nevertheless, the new machines did increase production, and Kentucky was one of the states to reap the benefits. In Kentucky were 65 cigar manufactures in 1929, making the state one of the top cigar producing locations in the United States, with the hope that the industry would be permanent, unless consumers changed their tastes in tobacco products. [Source: C. E. Landon, "Tobacco manufacturing in the south," The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 153, The Coming of industry to the South (January, 1931), pp. 43-53.]

For the African American workforce in and from Kentucky, the new technology had created a shift away from women being the majority of cigar industry employees. In 1930, there were 68 females and 70 males. The women were employed in three states: Indiana, Kentucky, and Ohio. More than half the women were employed in Evansville, with 35 stemmers, five laborers, four strippers, three day workers, a bunch breaker, janitress, and roller. Helen Brown was a cigar maker. The second largest group of 14 women were employed in Louisville in a variety of jobs that included three machine operators in cigar factories, laborers, stemmers, wrappers, and a filler, janitress, packer, roller, and stripper. Estella Shy was referred to as a "salesman" in a cigar store in Cleveland, OH. Lula Wright was a worker in a cigar factory in Jeffersonville, IN. [For more industry information see "Technological changes in the cigar industry and their effects on labor," Monthly Labor Review, vol. 33, no. 6, (December 1931), pp. 11-17.]

The 70 African American male employees from Kentucky were more geographically dispersed than the African American women from Kentucky. The men were located in 12 states: California, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Michigan, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. There were 15 men employed in Evansville, 11 in Chicago, eight in Louisville, with the remaining 36 men employed in 26 other cities. Seven of the men owned cigar stores: Robert Swanigan in Akron, OH; John Tate in Chicago; William Henderson and Harry White, who each owned a cigar store in Dayton, OH; Alonso Harris in Milwaukee, WI; and Metz Manion in Omaha, NE. Emmitt Williams was a boot black in a cigar store in Binghamton, NY. In Chicago, George F. Wilson was a cigar maker, and George T. Smith was the owner of a cigar making business. Major Bernard was a cigar maker in a factory in Dayton, OH, and Robert Voorhes a cigar maker in a factory in Cleveland, OH. Twenty-two of the men were porters in cigar stores and cigar factories, and there were 10 laborers and four janitors.

With the onset of the Great Depression and an already dwindling African American workforce in and from Kentucky, the employee numbers hit an all-time low of 10 in 1940. It was a drastic drop from the 138 who had been employed in 1930. Added to the downfall was the market loss; consumers were buying fewer cigars and more cigarettes. The manufacturing of cigars had completely flipped, with less than 20% of the cigars manufactured by hand, 75% machine made; and the remaining 5% made from a combination of hand and machine. Cigar production decreased from 6.4 billion in 1929 to 5.1 billion in 1939, while cigarette production increased from 122 billion to 181 billion.

In 1930, women were 80% of the cigar industry workforce, but not even this new hiring strategy had been enough to give the cigar industry an advantage, nor did the hiring of fewer African Americans. "The cigar industry in 1940 employed very few Negroes, only 6.9 percent of the estimated total number of wage earners being colored persons." In Kentucky, the number of African American employees in the cigar industry was two, the same as it had been in 1860, and the number working out-of-state was eight. The two employees in Kentucky were from Tennessee: Augusta Hinkle was an inspector in a cigar manufacturing company in Louisville, and Homer Mitchell was a janitor in a cigar store in Paducah. The eight out-of-state employees worked in New York, Michigan, Tennessee, Evansville (a cigar maker and two rehandlers), and Richmond, IN (where Henry Leavell owned a cigar store). The short-lived phase of high employment in the cigar industry was over for African Americans in and from Kentucky. [Source: "Wage and hour statistics," Monthly Labor Review, vol. 53, no. 6, (December 1941), pp. 1514-1537, Hours and earnings in the cigar industry, 1940. Quotation from p. 1517.]

*The terms slave, Negro, and colored all refer to African Americans.

*Stemmer - an employee who strips the stems from moistened tobacco leaves and binds the leaves together into books. Female stemmers were hired in the cigar industry to take the midrib out of tobacco leaves.

*Additional information from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention:

Cigars

African Americans and Tobacco Use

Surveillance for Selected Tobacco-Use Behaviors -- United States, 1900-1994